The historical significance of the dates August 29-31 to the global Jewish community can hardly be overemphasised. The three-day conference held at Basel, Switzerland in 1897, was to usher in a whole new phase in the history of modern Zionism, that eventually led to the the birth of Israel. Months of preparation had gone into ensuring the success of the conference. The chair of the conference, Theodore Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist who is better known as the father of modern Zionism, had thrown himself into the heart of the preparation, carrying out extensive correspondence with Zionist leaders from across Europe and distributing the agenda in every major European Jewish community.

By the eve of the conference a total of 204 delegates arrived from 15 countries, including the United States, Algeria, Palestine as well as Western and Eastern Europe. The sessions began at the Stadt Casino, a concert hall. A modern Zionist flag hung out at the entrance while the galleries were packed with visitors and correspondents from all the leading newspapers of Europe. Herzl began his speech amidst a roar of applause: “We are here to lay the foundation stone of the house which is to shelter the Jewish nation.”

“Antisemitism has given us our strength again. We have returned home…Zionism is the return of the Jews to Judaism even before their return to the Jewish land,” noted Herzl. He went on to emphasise that the older methods of piecemeal colonisation of Palestine deprived of any international recognition was no longer adequate. A new official body was required to deal with the Jewish question more forcefully. Thereafter, a Zionist organisation was established with the aim of a Jewish homeland that was “openly recognised, legally secured”.

The birth of modern Zionism did not in fact get the support of most Jews across the world at that time. “Zionism was a minority viewpoint in the Jewish community for a long time and only became a majority viewpoint after World War II,” explains historian James Gelvin in an interview to Indianexpress.com “There was a good reason for that because basically it asked people to abandon their homes, go thousands of miles away, to take up occupations like farming that they had never participated in before,” he notes further. Moreover, many Jews were uncomfortable with the idea of privileging Judaism over other forms of cultural identities they had.

Zionism was one among several other movements among the Jewish community in the 19th and 20th centuries. As Gelvin suggests, the reason Zionism survived was because of the backing it received from a powerful nation like Great Britain, even though not all Jews were in support of it.

Zionists before Theodore Herzl

While the modern Zionist movement can be traced to the writings of Herzl, the seeds of the ideology had been planted long before him. The term Zionism is derived from Zion, a hill in Jerusalem that widely symbolises the land of Israel. It rested on the belief that Jewish people must be resettled in their homeland in Jerusalem. Through the centuries of Jewish dispersion, Zion functioned as a binding component for the community’s social and religious experience. The movement emerged in the 19th century in response to growing anti-semitism and nationalism in Europe.

Political Scientist Michael Barnett in his article The Jewish Problem in International Society (2019), writes that “European societies had a Christian ‘self’, which meant that non-Christian people often became the ‘other’.” Anti-semitism in Christian Europe, writes Barnett, emerged from the belief that the Jews “killed Christ, are clannish and stiff-necked people, are a distinct race, are parasitic on society, and on and on.”

Advertisement

Before the 18th century, this othering of the Jews often resulted in European principalities, monarchies and states controlling them through severe segregation. From the 18th century onwards though European governments began to reconsider their relations with the Jews on account of the emergence of humanistic movements and ideologies such as the enlightenment, liberalism and secularism.

Consequently, the modernising societies of Western Europe Jews were allowed to venture out of their ghettos. Further, the emergence of nationalism in Western Europe during this time meant that the Jews were required to shed off their religious beliefs and drop the traditional alliances to Zion. To protect their newfound civic freedom therefore, Jews in Western Europe and the US agreed to prioritise their loyalties to the nation-state over their religious identities.

This was in stark contrast to what was happening in East Europe during this period. Historian Howard M Sachar in his book, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time (2013) writes that the three million Jews of Eastern Europe represented nearly 75 per cent of world Jewry in 1850. The largest number of Jewish Easterners were to be found in Russia where they were the “most despised and oppressed minority”.

Advertisement

Illustration of the pogrom in Kiev, 1881 (Wikimedia Commons)

Illustration of the pogrom in Kiev, 1881 (Wikimedia Commons)

In Tsarist Russia, Jews were ghettoised, denied any opportunities of livelihood and refused any share in the local government. Waves of pogroms between 1881 and 1884 and anti-semitic May laws of 1882 introduced by Tsar Alexander III deeply affected the community. The Jews of Eastern Europe reacted by fleeing westwards or building walls around their community to protect their way of life.

Consequently, some Jews saw Jewish nationalism as the answer to their problems. Barnett explains that Jewish nationalism took various forms. Some advocated cultural and regional autonomy, others argued for a form of diaspora nationalism in which Jews would strengthen their international bonds without necessarily demanding any political rights.

But the most important kind of nationalism that emerged among Eastern Jews during this period was Zionism. “Zionism’s popularity was directly related to the Jews’ wretchedness, which was why it had a much greater appeal in the East than the West,” writes Barnett. “And unlike some other forms of nationalism that would have forced states to accommodate transnational people in their states, Zionism and a Jewish homeland or state was consistent with the international diversity regime because Jews would now be housed in a separate, sovereign state.”

One of the first persons to formulate a framework for the zionist prophecy was an Orthodox rabbi from a little Sephardic community, Semlin, near Belgrade. Rabbi Judah Akalkai published a Ladino Hebrew textbook called ‘Darchei Noam’ (Pleasant Paths) in 1839 in which he wrote about the need for establishing Jewish colonies in the Holy Land as a necessary prelude to the Redemption. For the next four decades, Akalkai continued to publish his ideas and in the end settled in Palestine as a way to set an example.

Similar ideas were being propagated by Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer who served at a Polish speaking city called Thorn in East Prussia. In his multiple pieces of writings through the mid-1800s, Kalischer concluded that the salvation of Jews as foretold by the Prophets could take place through self-help and that they did not require the advent of a messiah, that the colonisation of Palestine must be carried out immediately and that the revival of sacrifices in the Holy Land was permissible. Kalischer urged a body of rich Jews to be formed who would undertake the colonisation of Zion. In response to Kalischer’s initiative a French Jewish Philanthropy provided the initial subsidy for a Jewish agricultural school in the Holy Land. The institution called Mikveh Israel (Hope of Israel) was established near Jaffa in 1870.

Advertisement

The forces of nationalism sweeping through Europe during this period also influenced the Jews to further ask for their own nation. “All of the Balkans for example were finding national roots during this time. The Burgarians, Serbs, Greeks were all invented identities and states. The Jews in that sense were not unique,” says Gelvin.

One of the most original Jewish responses to nationalism came from Moses Hess who belonged to an Orthodox Jewish family of Bonn in Germany. Influenced by the writings of Kalischer and that of the Italian nationalist Mazzini, he published the second volume of his work, Rome and Jerusalem in 1862 in which he insisted that what the Italians and others had achieved must be done by the Jews as well. “Only a national renaissance can endow the religious genius of the Jews…with new strength, and raise its soul once again to the level of prophetic inspiration,” he wrote (as cited by Howard Sachar in his book).

Advertisement

The Jewish pogroms of 1881 in Russia, often considered the worst of the pogroms in imperial Russia, convinced even those Jews who were inclined towards an approach seeking assimilation that emancipation and a national realisation of Jews were the only answers to their problems. Leo Pinsker, a physician from an ‘enlightened’ Jewish family of Odessa, was one of those who believed in the cultural assimilation and self-expression of Jews within a pluralist Russia. After the anti-Jewish outbreak of the 1881 though, he wrote a lengthy essay titled Selbstemanzimation (auto-emancipation) in which he argued that the “Jewish people had no fatherland of their own, no centre of gravity, no government of its own, no official representation.”

“There is something unnatural about a people without a territory, just as there is about a man without his shadow,” wrote Pinsker, although he attached no special importance to Palestine. That territory could be anywhere on earth but what mattered most was recognised nationhood on a piece of land. Pinsker quickly became one of the most admired men in Russian Jewry. He believed that the Jews of the West were required to provide leadership to his movement. However, he failed to elicit a response among the Jewish aristocrats of the West and was forced to turn to Eastern Jews for his Zionist movement.

Advertisement

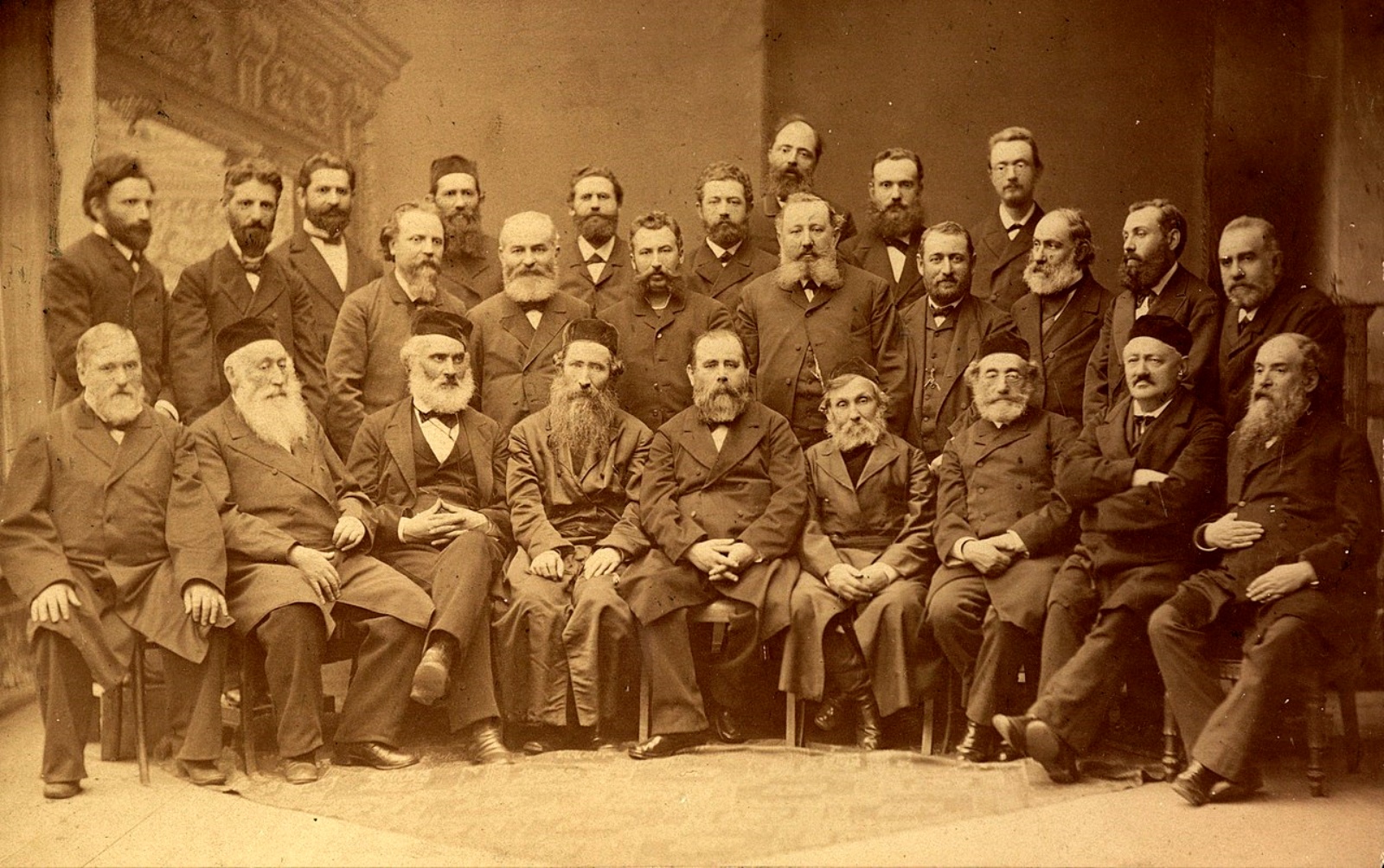

Participants of Katowice Conference, 1884. (Wikimedia Commons)

Participants of Katowice Conference, 1884. (Wikimedia Commons)

Consequently, by the time Herzl entered the stage of the Zionist movement, several small clubs and circles promoting Zionism had sprung up across Europe and even the United States. Collectively they were known as Chovevei Zion or ‘Lovers of Zion’. In 1884, Pinsker summoned a conference of these various Chovevei Zion societies at Kattowitz in Southern Poland. It established its headquarters at Odessa and Pinsker as its president was charged with directing a growing stream of emigrants to Palestine.

Theodore Herzl’s political zionism

The emergence of the writer and journalist Theodore Herzl in the 1890s was a landmark moment in the Zionist movement. Herzl is regarded as the spiritual father of the Jewish state and is known to have been the first person to lay out a practical and concrete plan of action to realise the Zionist desire of a Jewish nation.

Born in Budapest in 1860 in an affluent banking family, like Pinsker, Herzl too in his younger days was of the liberal view that religious and racial prejudices would disappear in an enlightened age. However, the anti-semitic wave of the 1880s and more importantly the suicide of a close friend, had a deep impact on his mind. From 1892 onwards, while he was working as a correspondent for a Viennese newspaper in Paris, he devoted more and more of his columns to anti-semitism in the French capital. He rejected most of his earlier ideas about Jewish assimilation and believed that Jews must remove themselves from Europe.

“Herzl believed that they needed diplomatic help in order to realise the dream of an autonomous Jewish state. So he spent most of his life shuttling from one prime minister to another, to emperors, sultans and more trying to get their support,” explains Gelvin. This was in contrast to the Practical Zionists who believed that they could realise their dream if they emigrated to Palestine and set up colonies there without first getting the backing of a great power.

In 1896, Herzl published his famed pamphlet, ‘Der Judenstaat’ (The State of the Jews). It was subtitled ‘An attempt at a modern solution to the Jewish question’. In the first chapter, Herzl argued that the Jewish question was neither a social nor a religious one. “It is a national question, and in order to solve it we must, before everything else, transform it into a political question, to be answered in the council of the civilised peoples,” he wrote. He further contended that Europe itself would cooperate in the Jewish departure and that international recognition for the rights of the Jewish people would have to come first. He also argued that although either Argentina or Palestine would be useful sites, the latter would be preferred on account of being the Jews’ “unforgettable historic homeland”.

Herzl is regarded as the spiritual father of the Jewish state and is known to have been the first person to lay out a practical and concrete plan of action to realise the Zionist desire of a Jewish nation. (Wikimedia Commons)

Herzl is regarded as the spiritual father of the Jewish state and is known to have been the first person to lay out a practical and concrete plan of action to realise the Zionist desire of a Jewish nation. (Wikimedia Commons)Sachar in his book explains that Herzl’s theory stood out also because for the first time a Zionist idea was formulated by a man of the world, “a distinguished political observer and broadly traveled journalist.” It introduced Zionism to European readers, editors, university men, statesmen and other moulders of public opinion in the language they were used to reading.

The initial reaction to Herzl was far from enthusiastic. The European press and several Jewish elites ridiculed his work right away. At the same time there were several Zionist societies that welcomed Herzl’s work with loud praise and invitations for holding lectures.

Although he did not live to see his dream of a Jewish state, Herzl’s biggest success lay in meeting and carrying out negotiations with leaders and statesmen of various nations including the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire who had turned down his offer to consolidate Ottoman debt in return for Zionist access to Palestine.

It was only in 1917 that the Zionist dream was finally realised and that too on account of British support. The Balfour Declaration issued by the British government during the First World War announced the establishment of a ‘national home for the Jewish people in Palestine’, which was then under the Ottomans. It was in discussion in the British cabinet soon after the declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire as a means to secure Jewish support in the war.

The Balfour Declaration had far-reaching consequences. It led to increased support for Zionism from Jewish communities across the world and finally led to the creation of Israel in 1948. Some scholars have argued that even when the idea of Zionism was supported in creating a Jewish state it was rooted in anti-semitism. The American journalist Peter Beinart writing for The Guardian in 2019 suggests that “some of the world leaders who most ardently promoted Jewish statehood did so because they did not want Jews in their own countries.” He adds, “before declaring, as foreign secretary in 1917, that Britain “view[s] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”, Arthur Balfour supported the 1905 Aliens Act, which restricted Jewish immigration to the United Kingdom.”

Ironically, the most ardent opposition to the Balfour Declaration came from a Jewish member of the British Cabinet, Lord Edwin Montagu who rallied against the “mischievous political creed” of Zionism. In a memo written to his fellow cabinet members in August 1917, Montagu argued that the proposal would be “anti-semitic in result and will prove a rallying ground for anti-Semites in every country in the world.”

Critique of Zionism

Active criticism of Zionism among Jews existed as early as the 19th century and emerged in response to the writings of those like Hess, Pinsker and Herzl. Religious anti-zionists denied the contention that Jews constituted a nation. The spiritual leader of 19th century German Orthodox Jews at Frankfurt, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch is known to have said that the active promotion of Jewish emigration to Palestine was a sin.

It is only after the holocaust and the Second World War that support for Zionism spread across the Jewish diaspora. Even then, pockets of resistance to the Zionist movement remained. The Neturei Karta, a Jewish sect who were one of the first to have settled in Jerusalem and have stuck to an orthodox Jewish way of life, viewed with suspicion the waves of Jewish immigration to Israel since the 1880s. They resented the new arrivals and believed that Jewish redemption could be brought about only by the Jewish messiah. Since 1948, they have refused to become Israeli citizens and have been adamant in their refusal to pay taxes or join the army. At present, they are known to be the Jewish world’s most outspoken critics of Zionism. They deny the legitimacy of the Israeli government and have often expressed their protest by publicly burning the Israeli flag.

In more recent years, critics of Zionism have concentrated upon the continued expansion and occupation of Palestine by Israel. In the late 1980s a group of Israeli historians who referred to themselves as the ‘new historians’ agreed to re-evaluate the Zionist narrative. Journalist Ethan Bronner writing for The New York Times in 2003 suggests that the “new historians had an agenda- promoting the peace process then beginning.” While they were initially dismissed as self-haters and even traitors, the new historians gained popularity and respect from the 1990s.

The original group of new historians included Benny Morris, Ilan Pappe and Avi Shlaim. Shlaim, who was born in Baghdad in 1945 to an Iraqi-Jewish family, recounts in a paper written in 2001 that his family was well integrated into Iraqi society and did not have any sympathy for the Zionist movement. However, the establishment of the state of Israel caused a backlash against Iraqi Jews and his family was forced to flee and resettle in Israel. In his writings, Shlaim questioned the conventional Zionist version of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In his book Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions and Refutations, (2020) which is a collection of essays that Shlaim wrote over the past 25 years, he refers to Zionism as a public relations exercise. “Zionist spokesmen skillfully presented their movement as the national liberation movement of the Jews, disclaiming any intention of hurting or dispossessing the indigenous Arab population,” writes Shlaim in an article in 2011.

Most Read

Gelvin explains that “there are some people in Israel who are motivated by the religious ideology of Zionism who call the West Bank Judea and Samaria which are Biblical names for the territory. They do not want to give up on one bit of the land.” “Then there are others like the current prime minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu who need the support of religious Zionists in order to maintain a ruling coalition,” he says. “Netanyahu’s coalition is made up of extreme right wingers and religious zealots who believe in expanding Jewish settlements in Palestine. Some cabinet members are even in favor of expelling the Palestinians from the West Bank,” argues Gelvin.

Further reading:

Michael Barnett, The Jewish Problem in International Society, in ‘Culture and Order in World Politics’ ed. Andrew Phillips and Christian Reus-Smit, Cambridge University Press, 2019

Howard M. Sachar, A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2007

Avi Shlaim, Israel and Palestine:Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations, Verso, 2020

"Idea" - Google News

October 22, 2023 at 01:39PM

https://ift.tt/MnE9PKO

Zionism: How a movement opposed by most Jews spawned the idea of Israel - The Indian Express

"Idea" - Google News

https://ift.tt/AU5LQ14

https://ift.tt/A51snVy

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Zionism: How a movement opposed by most Jews spawned the idea of Israel - The Indian Express"

Post a Comment